Neurodivergent Gumbo #8

Disney’s Pocahontas — Pot 2: The Peace Treaty Bride

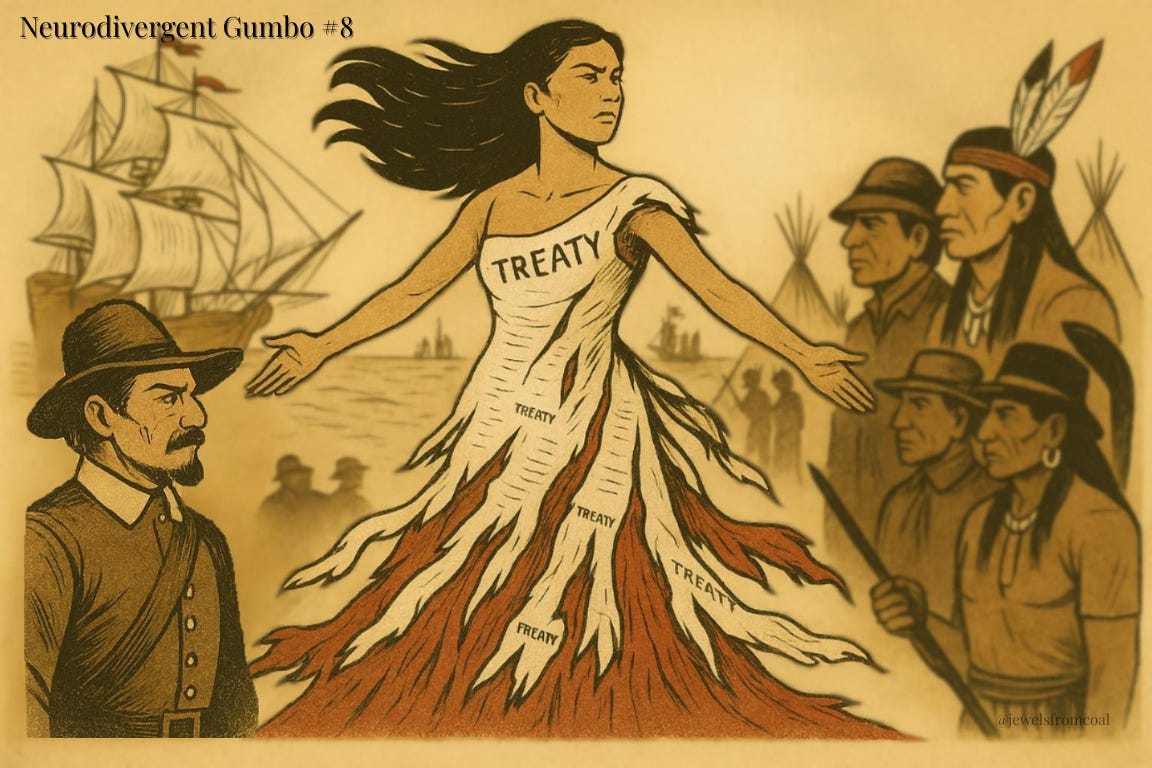

In Pot 1, we traced how conquest carved its way through land and lives. Now, we stir the quieter weapon: patriarchy. When brute force fades, societal conformity — through marriage, obedience, and treaties — keeps the empire in place.

Patriarchy, Marriage & Possession

Pocahontas is introduced as her mother’s daughter — wild, free, attuned to the world around her. Her father, Chief Powhatan, insists she marry Kocoum: steady, reliable, safe. It’s framed as the responsible path, the one that will ensure stability for the whole tribe. In other words: conformity through patriarchy.

Welcome to the Disney formula for the 90’s. Fathers are the guardians of tradition. Daughters are restless, different, “meant for more.” The community is cast as too rigid to see beyond convention, so the heroine has to push against her father to save them all. It’s not cultural accuracy — it’s comfort-zone storytelling.

We’ve seen this in later Disney undertakings with its princesses. Moana’s father, Chief Tui, uses the exact same playbook: safety through staying put, conformity for survival, patriarchy as protection. Moana — like Pocahontas — feels the pull of something beyond her father’s order. The message repeats: fathers know best until daughters prove them wrong. And when daughters win, they don’t topple patriarchy — they become the exceptions within it. But that’s Disney’s world. The reality was far more complex.

Indigenous Realities & Erasure

But here’s the erasure: many Indigenous cultures weren’t strictly patriarchal. The Haudenosaunee Clan Mothers appointed chiefs. Cherokee descent passed through the mother’s line. Pueblo women controlled land. Even among the Powhatan, women held influence in agriculture, trade, and family decisions. The Disney narrative flattens that richness into a Western default: father leads, daughter rebels, men hold authority until proven otherwise. Kids watching absorb this as universal truth.

The necklace scene doubles down on patriarchy as possession. When Kocoum tears the necklace from Pocahontas’s neck in his final scene, the symbol of her betrothal shatters. It’s treated not as her choice, but as a transfer of ownership. The patriarchal contract is broken by force, leaving her ‘available’ for John Smith. Marriage, in this frame, isn’t partnership. It’s property.

And look at the pattern beyond Pocahontas. In The Princess and the Frog, Tiana’s father is absent, his legacy reduced to bootstrap wisdom and a dream of owning a restaurant. The patriarch is replaced with capitalism itself: work hard, sacrifice, and maybe you’ll earn your dream. Her mother? Pressing her to marry, to give her grandchildren, to find fulfillment in the domestic role. No matter how you slice it, the lesson circles back to patriarchy: women are defined by marriage, by children, or by exceptional labor.

(I’ve stirred this pot before in my Gumbo dive on The Princess and the Frog — if you want the full ladle of that conversation, go back and sip from those posts.)

Note to the Reader (a tasting for later)

Moana and Tiana both deserve their own deep Gumbo stirrings — Moana for how Disney flirts with matriarchy but still returns to the father-daughter struggle, and Tiana for how bootstrap theory replaces patriarchy with capitalism. But for now, the throughline is clear:

Disney trains kids to see patriarchy as natural, inevitable, and eternal. Fathers rule, daughters resist, and women’s choices are framed as deviations from the “safe” order rather than inheritances of their own cultural power.

I’m not sure I’d want to be a princess if I was able to articulate these thoughts. I honestly felt the conflict, but didn’t know what to do with it. Not to mention that nothing is said of womanhood or motherhood. Children born as female in heterocentrist households are continually fed the notion of finding a husband, a wedding where you are celebrated. And then what?

“Happily Ever After” is the worst phrase to end a story.

And if children born female are being taught to expect wedding bells and a man to take care of you, then what are men being taught? And what happens when life gives you lemons? And heaven forbid you THINK outside the box. What has it done for anyone?

Hey there: I want to say here that I realise this series is heavy on binary language. This is where I am now, and I will evolve, and so too will my language. Ride with me as I evolve! 😊False Peace & Soft Conquest

Disney claims Pocahontas is about unity: “If we don’t learn to live with one another, we will destroy ourselves.” On paper, that’s noble. In practice? The story rigs the scales so the colonizers walk away with the better end of the stick.

The film leans on a Romeo and Juliet frame — two lovers from different worlds, their union offering the chance for peace. But this isn’t family drama; it’s colonization. Love here doesn’t neutralize power, it hides it. If John Smith dies, England sends more ships. If Pocahontas dies, her people lose not just a daughter, but the fragile balance of their community. The risk isn’t equal, but the movie pretends it is. This romance doesn’t neutralize power — it sets the stage for the next tactic.

And how do the colonizers “bridge the gap”? Through the oldest colonial trick in the book: mansplaining as soft conquest. John Smith arrives not asking but assuming: “We are better than you. You aren’t doing it right, let us show you.” That’s the culture-stripping Disney frames as mutual understanding. But what’s really happening is the honey-over-vinegar tactic — Pocahontas shielding Smith with her body, literally becoming the sweetener that persuades her father and her people to stand down. The colonizers don’t have to force their way in if they can charm their way in. And Smith’s quiet smirk afterward is the receipt.

The film ends with Smith sailing back to England, wounded but noble, while the English leave “for now.” It suggests peace has been earned. But history tells us what came next: return, expansion, violence, displacement. This isn’t peace. It’s a pause. A soft conquest disguised as harmony.

Interlude: Collaboration, or Assimilation?

Disney loves to sell the idea of harmony. In Pocahontas, John Smith promises to “teach” her people, to share his ways, to “build a new world together.” On the surface, it sounds like collaboration. But look closer: there’s no real exchange happening. No curiosity, no willingness to learn from the Powhatan. It’s one-way assimilation — his way, his language, his tools.

This is the colonizer’s default: our way is better, your way must go.

That message doesn’t stop with the movie. It bleeds into the mythology we’re taught in school. Take the “First Thanksgiving.” We’re handed this picture-book story of Pilgrims and Wampanoag sharing a meal in gratitude and friendship. The reality? It was a temporary truce, born from the colonists’ desperation and the Indigenous people’s generosity. A short-lived pause, not a new tradition. Within years, violence escalated, land was seized, and that so-called “thanksgiving” turned out to be a prelude to war.

And yet, millions of kids are raised on the sanitized version — harmony, cooperation, mutual respect. It’s the same fantasy Pocahontas sells: that the colonizers came to share, not to strip away.

So when Disney fanatics make their annual pilgrimage to the parks, when they plaster Mickey ears on their cars, they’re not just buying nostalgia — they’re buying into a narrative that has always been one-sided. Collaboration as long as you assimilate. Peace as long as you step aside. Gratitude as long as you don’t resist. This mythology is not in a textbook. Yet, it is commercialized, packaged, and marketed by age group. And this has been done since the mid-1920’s.

Sidebar: By the time Disney made Tarzan, they didn’t even bother splitting the narcissist from the greedy exploiter. They gave us Clayton. John Smith’s vanity plus Radcliffe’s greed rolled into one body. Different jungle, same colonial disease. <Ugh>

.

So yes, we should learn to live with one another. But in Disney’s telling, “living together” always means one side bends, and it’s never the colonizers.

“Colonization didn’t grow from greed alone. In England, the poor were being pushed off their land, rivals like Spain were swimming in stolen gold, and religion had become a weapon for expansion. Colonies weren’t just about opportunity; they were about control. And when you mix survival anxiety with supremacy theology and national competition, greed curdles into something worse — a virulent malice that strips culture and calls it destiny.”

And the control of narrative didn’t end in the 17th century — it just changed form.

Disney/ABC’s recent firing of their late-night host over a comment protected by “free speech” isn’t just headline drama — it’s part of the same pattern we see in Pocahontas (and beyond). Because what looks like “freedom of expression” is often constrained by what protects power, image, and profit.

Corporations will allow certain narratives — the nice, palatable, “everyone loves one another” type — but push aside or punish ones that disrupt who holds control.

Just like in Pocahontas, where the film presents “learning to live together” and “understanding each other” as the moral high ground — those messages are acceptable because they don’t challenge colonizer supremacy. What does challenge it — real reparations, Indigenous sovereignty, critique of colonizer guilt — is rarely permitted in Disney-approved space.

Free speech becomes free only for those whose words align with the power structure. For everyone else, the boundaries are rigid and enforced (quietly or loudly).

So, when a late-night show host gets fired for crossing those invisible lines, it’s a reminder that storytelling — even jokes or commentary — still happens inside a glass cage designed by whoever owns the narrative.

In Pot 3, we’ll follow these myths into the present — through nostalgia, merchandise, and the cultural narratives we still breathe in today. Stir the pot with me — share this, comment, or bring your own ingredients to the table.