Neurodivergent Gumbo #9

Disney’s Pocahontas — Pot 3: Erasure & Resistance

Previously in Neurodivergent Gumbo…

Pot 1: Inheritance of Violence

We began with Disney’s opening frames—ships slicing the Atlantic, conquest dressed up as adventure. Forts rose like monuments while land and people were framed as waiting to be claimed.

The story didn’t start with love; it started with invasion

Pot 2: The Peace Treaty Bride

Next came the quieter weapons: marriage, patriarchy, obedience. Pocahontas becomes the bridge between worlds, her body and choices politicized as tools for “peace.”

When the sword is sheathed, the marriage contract takes its place.

Now, Pot 3: Erasure & Resistance

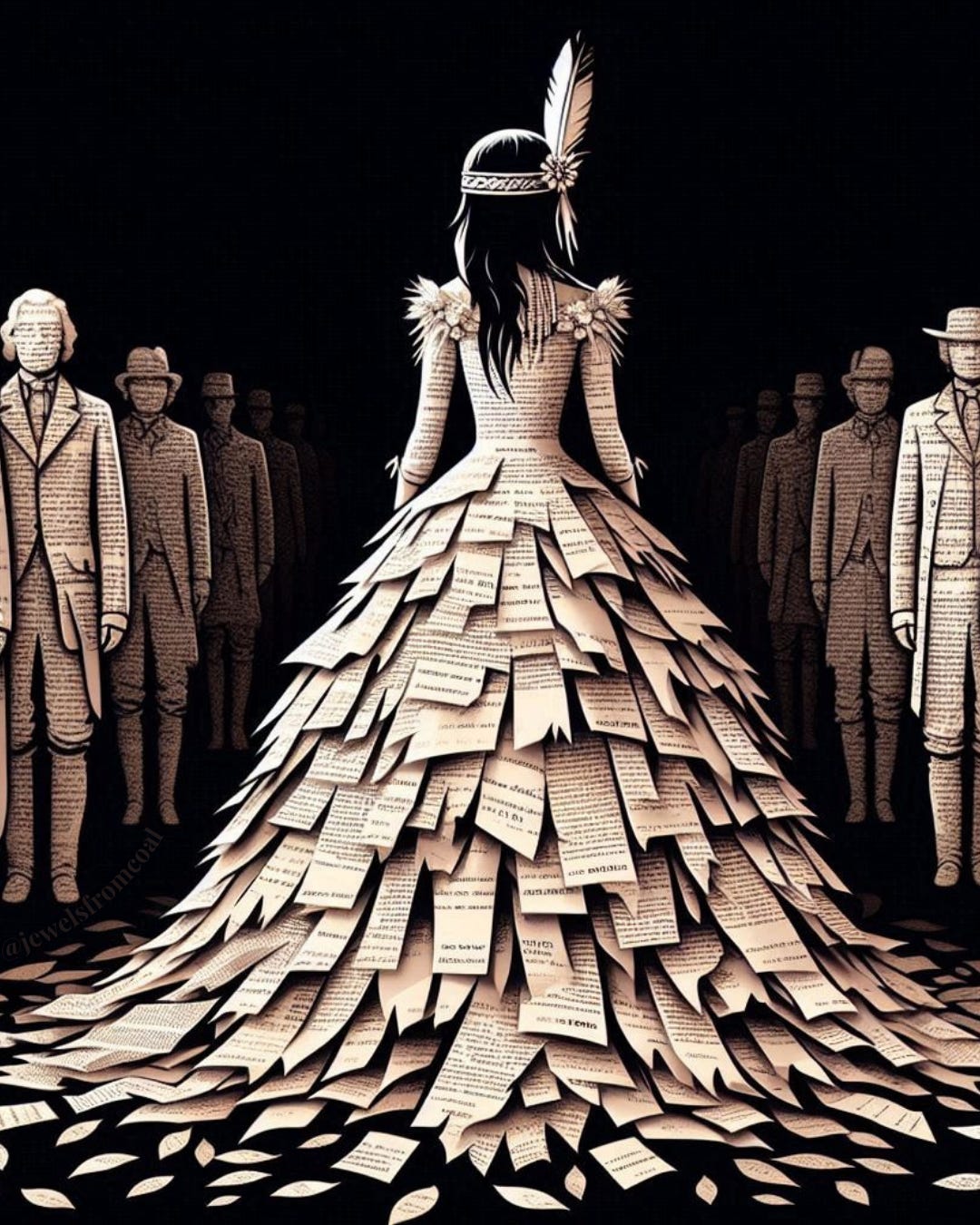

With conquest and assimilation set, Disney sustains the myth through what it hides—erasing victories, rewriting truths, and framing conquest as destiny. Pot 3 uncovers these silences and honors survival as resistance.

Subliminal Messaging & Visual Framing

The conquest isn’t just in the dialogue or the plot. It’s in the pictures. Disney knows how to preach without words, and Pocahontas is full of subliminal sermons.

Take the sunset framing: as Powhatan leads his people, the sky burns behind them, but the camera pulls wide to show the colonizers looming above, perched on higher ground, gazing down. The visual says what the script won’t: they are larger, stronger, inevitable. Children watching absorb that without realizing — power tilts upward, Indigenous people are framed downward.

Or the pristine rivers. When Smith splashes his face, it looks like he’s stumbled into untouched Eden. The irony, of course, is that the water was pure because no one was desecrating it — because Pocahontas ’s people lived in relationship with it. But the framing makes it seem like discovery, as if it only came into being once Smith laid eyes on it. That’s how you teach kids that land is there for the taking.

Even the angles of the fort are telling. It rises in jagged lines, smoke pluming above it, shot in heroic perspective as if it’s an accomplishment. The fact that it required destruction — trees felled, earth stripped, harmony broken — is hidden beneath triumphant music. The fort is not shown as scar; it’s shown as monument.

And then there’s Pocahontas herself. Her movements are always fluid, tied to wind, water, light. Smith and Radcliffe, by contrast, are angular, rigid, shot from below to look commanding. These visual cues whisper a lesson: Indigenous power is mystical, soft, natural — but colonizer power is structured, solid, “real.” The film never says that outright, but the framing trains children to believe it.

This is why Pocahontas works not just as story but as subliminal indoctrination. The camera tells kids what the dialogue cannot admit: colonization is destiny, and the beauty of the land is just waiting to be claimed.

Missed Truths

Disney’s Pocahontas is built on absence as much as presence. What the film doesn’t show speaks louder than what it does.

Where are the Indigenous victories? The Powhatan Confederacy resisted English encroachment for decades, winning battles, negotiating on their own terms, and forcing colonists to recognize their power. The film erases this history, reducing them to passive recipients of wisdom from a daughter and mercy from a colonizer. Children grow up thinking Indigenous people only softened, never resisted.

Where is the medicine? When Smith is wounded, the script insists he must sail back to England to be saved. The implication is that Indigenous knowledge was insufficient. But the Powhatan — like countless nations — had deep traditions of healing through plants, ceremony, and community care. The choice to deny him that care erases Indigenous science and sustains the myth that European medicine was superior.

Where is the truth of the aftermath? The movie ends with Smith leaving and the English “sailing away,” as if the story closes on hopeful compromise. But history tells us otherwise: the English came back, in greater numbers, with sharper hunger. Land was taken, communities displaced, blood spilled. The so-called “peace” Disney portrays was a pause before devastation, not a resolution.

This is how empire works: not only through violence, but through erasure. Erasing victories. Erasing knowledge. Erasing the brutality of what came next. The absence becomes its own kind of violence — the violence of forgetting.

And children who grow up on this story internalize that erasure. They learn to believe in compromise that never was, peace that never lasted, and conquest that looks like romance.

Sidebar: Why CRT Matters

Critical Race Theory isn’t about shaming individuals — it’s about examining systems. CRT helps us see how racism and power aren’t just interpersonal problems; they’re baked into the structures of law, education, media, and national mythology.

When applied to stories like Pocahontas, CRT illuminates how colonial myths get repackaged as “romance” and “progress,” while Indigenous voices are erased or sidelined. Without this lens, these narratives pass as harmless entertainment. With it, we see the machinery of cultural dominance at work.

Reflection: Survival as Defiance

Watching Pocahontas with new eyes, I see more than a love story. I see a starter pack for conquest dressed in song. I see how women of color are turned into bridges, how harmony with nature is eroticized, how conquest gets softened until children think it looks like peace. And I see myself in the frame — my DNA, my history, my survival woven through the same system of control.

That realization is traumatizing. To know that survival for my ancestors often meant softening violence, absorbing blows, becoming the bridge so the community could live another day. It’s a truth that doesn’t just live in textbooks; it lives in my body.

And yet, here I am. Living, naming, loving.

Some might call me a hypocrite for critiquing these systems while being married to a white woman. But my marriage is my choice — freely given, rooted in love, and nurtured in defiance of a world that once outlawed it. If white supremacy had its way, that choice would be stripped from me. And that is the difference: conquest never allows choice. Love does.

This is why I write, why I stir these pots. Because storytelling itself has been captured by conquest. Even our cautionary tales are packaged and sold for profit. Disney can sell colonization back to us as romance, and even my own critique has to be carried through platforms built on capitalism’s bones. That doesn’t make the work hypocrisy. It makes it survival in a system that insists even resistance must turn a profit.

So no, this isn’t hypocrisy. It’s defiance. It’s refusing to let the systems of virulent malice decide who I can love, how I can live, or whether my story gets told.

Disney can keep its sanitized fairy tales. I’m stirring the real Gumbo here — the one where truth tastes bitter, but it also nourishes. The one where survival is testimony, and love itself is rebellion.💎

Jewels, thanks so much for all these essays on deconstructing movies. Once past grammar school, I was uncomfortable with the whole Pocohantas story. This was before I knew the truth of the genocide of the First Nations. Your analysis is crystal clear and my whole body recognizes the veracity of your words. I get why you didn't welcome my idea of you as a University professor, however, I wish your writing had been available to me when I was a student. I'm grateful to read your work now. May your writing reach lots and lots of people and awaken them, as it does me. As for anyone commenting about your marriage to Amy with anything other than well wishes, they better not be sitting near me.